About Us

da 150 anni vestiamo l’Italia

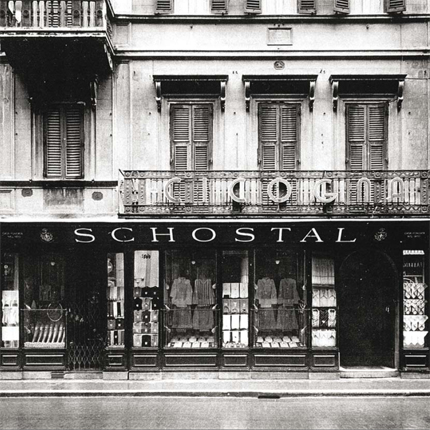

Ha compiuto da poco 150 anni, aprì infatti i battenti a via del Corso, nel dicembre 1870, subito dopo la breccia di Porta Pia. S’intitolava “Alla città di Vienna. Schostal”, nome quest’ultimo accattivante perché nordico, mitteleuropeo, ma anche la posizione prescelta era strategica: nel punto centrale dello shopping mattutino e del passeggio pomeridiano.

Quando, a fine Ottocento, le signore avevano bisogno di un paio di calze, bianche o colorate, in filo di Scozia, lana o seta, o di una sottana, di un copribusto o di una cuffia, era inevitabile che facessero una sosta nel settore intimo donna di Schostal. Il prezzo delle calze oscillava dalle 2 lire per quelle di cotone fino alle 22 lire per quelle di seta; con 350 lire si poteva acquistare il corredo da sposa più economico.

Questi e altri prezzi sono contenuti in un catalogo che il direttore e poi proprietario del negozio, Lazaro Bloch, distribuiva ai clienti più affezionati e che oggi è una fonte preziosa d’informazioni.

Vi si legge che quanto a camicie da uomo, il negozio era maolto fornito.

Quelle in vero shirting costavano dalle 5,5 alle 10 lire, mentre le camicie di tela batista, ricamata a mano, anche più di 30 lire.

Oltre alla camicie, si vendevano anche gli accessori: colli, polsini e “davanti”.

Le cravatte, che erano bianche, costavano una lira ciascuna. I prezzi erano fissi, cosa non usuale per l’epoca. Era prevista la spedizione a domicilio, anche fuori città e le casse e gli imballaggi erano gratis; la merce non soddisfacente poteva essere restituita e veniva cambiata. Se il nome del negozio era austriaco (corrispondeva a quello di due sudditidell’Impero austro-ungarico, Leopold e Guglielmo Schostal), Lazaro Bloch era torinese, di religione ebraica.

Insieme con altri tre dipendenti della ditta di Vienna, intorno al 1870 aveva fondato una società che rilevò le numerose filiali di Schostal in Italia, ivi comprese le ultime tre, a Roma, Napoli e Palermo.

It just celebrated his 150th birthday. It opened in Via del Corso in December 1870, just after the breach of Porta Pia. It was named “To the city of Vienna, Schostal”; this last name, being a northern, mittleuropean name, was captivating, but the chosen position was also strategic. Within the centre of morning shopping and afternoon walking.

When, at the end of the 19th century, ladies needed white or coloured stockings, made out of cotton thread, wool or silk, or they needed petticoats or corsets or bonnets, it was inevitable for them to stop at Schostal’s women’s lingerie department. Stockings prices fluctuated between L. 2, for cotton stockings, and L. 22 for silk ones; with L. 350 you could buy the cheapest bridal trousseau.

These and others articles are contained in a catalogue that the director, then owner of the shop, Lazaro Bloch, distributed to his most affectionate clients and that today is a precious source of inspiration.

About men’s shirts, you can read that the shop was wellstocked. Those made out of true shirting cost from L. 5,5 to L. 10, while the shirts in batiste cloth, hand-embroidered, could cost more

than L. 30.Beside shirts, accessories were sold:

collars, cuffs and “fronts”.

Ties were white and cost L. 1 each. Prices were fixed, and this was unusual for the times. Home delivery was provided for, also out of town, and boxing and packaging were free; if you were not satisfied by the articles you received, you could return them and they were changed.

If the name of the shop was Austrian (it was the name of two Austro-Hungarian Empire’s subjects, Leopold and Guglielmo Schostal), Lazaro Bloch was from Turin and his religion was Jewish.

Together with other three employees from Vienna’s firm, around 1870 he established a company which took over Schostal’s numerous Italian branches, the last three in Rome, Naples and Palermo.

Naturalmente mantenne nell’insegna il vecchio e già noto nome di Schostal e ciò, molti anni dopo, nel 1939, all’epoca delle leggi razziali, provocò notevoli grattacapi agli eredi, in quanto le autorità fasciste, sospettando che esso fosse di origine ebraica, decisero che l’insegna andava tolta. I fratelli Bloch si opposero, sostenendo tra l’altro che il nome, non loro, era stato qualche volta utilizzato come sigla (Società Commerciale Hongroise Objets Soie Toile Articles Lainage), e l’ebbero vinta. Nell’insegna rimase anche la scritta “Alla città di Vienna” che, tanto per cambiare, nel 1914 aveva scatenato l’ira di un gruppo di interventisti, e scomparve solo quando la mostra originaria è stata sostituita da quella al neon, attuale. È una delle poche cose cambiate nella fisionomia di un negozio le cui vetrine e le cui stigliature sono rimaste quelle di ieri. Vetrine incorniciate da listelli di ottone; scansie, semplici e funzionali, spazio di appoggio per tutte le scatole, da cui continuano ad emergere, oggi come ieri, bene appilate, maglie e camicie. A memoria dei proprietari (la famiglia Bloch è giunta alla quarta generazione), scaffali e banchi sono stati soltanto ripuliti, non cambiati, mentre è relativamente nuova la copertura a vetri dei banchi di vendita. Ha sempre fatto parte, del resto, della politica commerciale dei proprietari adeguarsi ai tempi senza scosse né traumi; il che ha permesso al nome del negozio di entrare a far parte della memoria collettiva delle famiglie romane, dove viene ancora associato con qualcosa di rassicurantemente nordico: tedesco o elvetico. Al transfert hanno sicuramente contribuito il nome e la personalità di Giorgio Bloch, che ha diretto il negozio prima e dopo l’ultima guerra. Uomo colto, oltre che commerciante, amico di artisti, musicisti, autori di teatro, con i quali s’incontrava nel suo ufficetto, due metri per due, in fondo al negozio di via del Corso. Restano foto, dediche, Pirandello: “All’amico Bloch”, Alfredo Casella: “Al salvatore dei musicisti”, e così via. Ha avuto a suo tempo gli onori della cronaca, l’iniziativa che Giorgio Bloch assunse nell’immediato dopoguerra, quando imperversava la borsa nera. Chiuse il negozio avvisando i clienti che in quella situazione non avrebbe potuto vendere in modo onesto. Riaprì quando la situazione cominciò a normalizzarsi, ma svendette quanto gli era rimasto a prezzi d’anteguerra e da quel momento fece punto e a capo.

Obviously it maintained in its store sign the old and already well-known name Schostal, and this, many years later, in 1939, at the times of martial laws, caused the heirs a lot of troubles, because Fascist authorities suspected it to be of Jewish origin and so they decided that the store sign was to be taken off. Brothers Bloch opposed it, asserting that, among other things, the name had been sometimes used as an acronym (Societé Commerciale Hongroise Objects Soie Toile Articles Lainage), and they got away with it. Also the writing “To the city of Vienna” that in 1914, just for a change, made a group of interventionists furious, remained in the store sign. It disappeared only when the original store sign was substituted with the current neon-sign. This is only one of the few things that changed in the physiognomy of a shop whose shop windows and hackling are the same of yesterday’s. Shop windows framed in brass fillets; simple and functional shelves, supporting surfacesObviously it maintained in its store sign the old and already well-known name Schostal, and this, many years later, in 1939, at the times of martial laws, caused the heirs a lot of troubles, because Fascist authorities suspected it to be of Jewish origin and so they decided that the store sign was to be taken off. Brothers Bloch opposed it, asserting that, among other things, the name had been sometimes used as an acronym (Societé Commerciale Hongroise Objects Soie Toile Articles Lainage), and they got away with it. Also the writing “To the city of Vienna” that in 1914, just for a change, made a group of interventionists furious, remained in the store sign. It disappeared only when the original store sign was substituted with the current neon-sign. This is only one of the few things that changed in the physiognomy of a shop whose shop windows and hackling are the same of yesterday’s. Shop windows framed in brass fillets; simple and functional shelves, supporting surfaces for boxes from where, today like yesterday, shirts and vests emerge well piled up. For what the owners can remember (Bloch family reached the fourth generation by now) shelves and counters were just polished, not replaced, while counters’ glass covering is rather new. Besides, the commercial policy of the owners was always that of keeping up with the times without shocks or traumas; this allowed the name of the shop to enter Roman’s families collective memory, where it is still associated with a reassuring Nordic feeling: German or Helvetian. The name and personality of Giorgio Bloch, who directed the shop before and after the war, surely contributed to the transfer. He was a cultured man, beside being a tradesman; he was friend with artists, musicians, playwriters, with whom he met in his tiny office at the back of Via del Corso shop. Pictures and dedications remain. Pirandello: “To my friend Bloch”. Alfredo Casella: “To the musicians saviour”. And so on. When the black market was the rage of the early post war period, the chronicles did Giorgio Bloch’s initiative justice. He closed the shop, informing the clients that under those circumstances he could not sell honestly. He opened again only when the situation was going back to normal, but he undersold at pre-war prices the articles left from before the war and, at that moment, it was full stop and a new paragraph for him.